How Compassion Helps Us Reimagine Childhood Wounds

Over the years, my approach in teaching type has been framed by two things: how our imperfect early holding environments shaped our sense of self, and why self-compassion is essential in the journey of self-understanding. I’ve attempted to redefine the Enneagram’s so-called Childhood Wounds less as actual trauma and more in line with an experience of confirmation bias—confirming to the tenderness of our young egos that our true Essence has dissipated and been replaced with our type. This loss of innocence is actually a necessary part of our story. It’s the figurative doorway that we pass through as we are welcoming in the tragic pain of being human.

I call this our Kidlife Crisis.

Perhaps rehabilitating the Original Wound, Childhood Wound, and the Lost/Unconscious Childhood Messages language by substituting it with Kidlife Crisis offers a more compassionate approach to understanding why we are the way we are.

Perhaps reframing these so-called Childhood Wounds as the inevitable Kidlife Crisis allows for us to understand this integral passage as one of the most crucial stages of our earliest experiences of becoming.

Perhaps embracing our Kidlife Crisis is the very thing we need to help heal the brokenness in some of our relationships with a parent or caregiver. Honest awareness of our Kidlife Crisis and how it has fortified type as a kind of confirmation bias is one of the most crucial steps in belonging. We have to understand why we are the way we are if we are to practice compassion toward every aspect of ourselves, even the parts we’d rather not identify with.

Could this be yet another way then to answer the question, What do we mean by ‘type’*. [*I picked up this “dominant in type . . .” language from my dear friend and professional colleague, Dr. Avon Manney. It’s one of the ways our phraseology of type can affirm that though we have a dominant type we still possess the energies and raw materials of all nine types within us.]

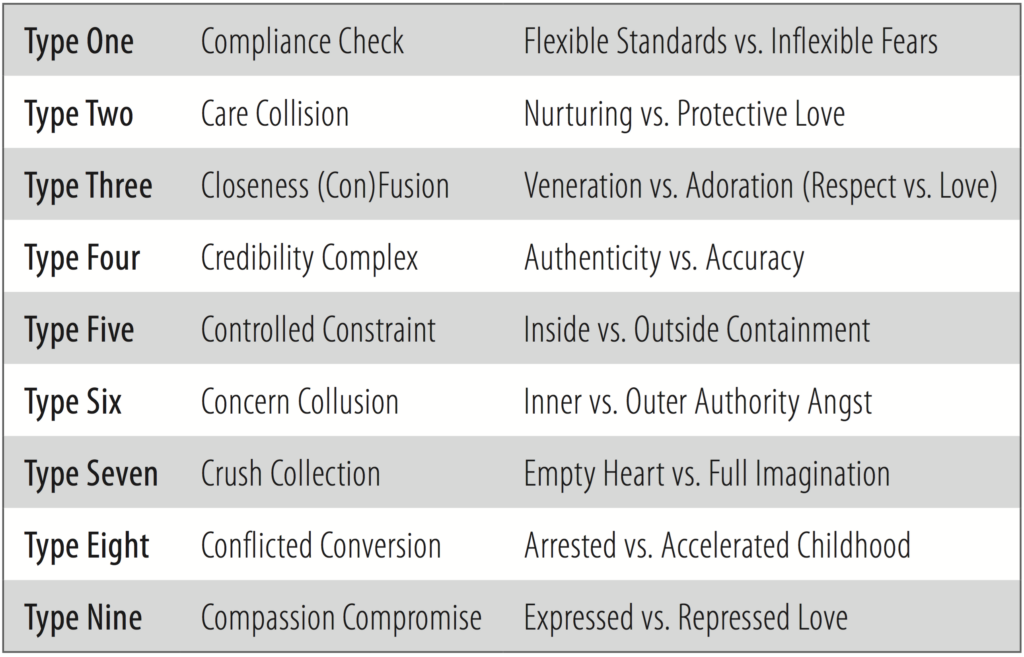

Reframing these so-called Childhood Wounds to Kidlife Crises makes room for compassionate self-embrace. It’s important to affirm that even these Kidlife Crises belong to our whole selves. Learning to accept them is key in learning to accept the whole of our stories. Let’s consider how these inner conflicts play out for each type.

Type One’s Compliance Check: Flexible Standards vs. Inflexible Fears

For those dominant* in type One, this Kidlife Crisis was an inner Compliance Check. Born to be a source of goodness, their Basic Fear of being innately corrupt caused Ones to become obsessively submissive to their inner critic. This resulted in Ones being some of the most principled people. All the little Ones wanted was to be loved (just like all of us in nine different ways), and they intuited they would have to earn this love through compliance to the expectations set by their caregivers. The crisis occurred when those expectations were unclear or inconsistent. Maybe their family moved around changing homes or cities, or maybe other siblings were introduced into the household, creating changing, arbitrary, and otherwise flexible standards. Whatever the case, the flexibility of their holding environments created unpredictable expectations that the One’s inflexible fear of being intrinsically flawed couldn’t deal with. There was a collision of flexible external standards and inflexible fears of innate corruption. As a result, Ones learned to turn inward, accessing their own resources for devising the criteria for how to live and causing them to double down on their inner compliance for what it means to be principled. If they could now just live into their own (albeit unrealistic) standards and expectations for perfection, then maybe they’d finally be less debased than their fear suggests.

Type Two’s Care Collision: Nurturing vs. Protective Love

Poor little Twos suffered their Kidlife Crisis as a Care Collision, the impact of love’s rival expressions: protection and nurturing. Can you imagine young Twos putting their childlike hearts into the world while generously giving themselves away? What benevolence! The power of their innocence and the force of their presence opened up the hearts of all those in their emotional orbit. They made the rest of us feel as if it was okay to get in touch with the tender parts of our emotional selves. But there was a caregiver who watched all of this with concern (conscious or unconscious). They were afraid that someone would take advantage of the Twos’ open-heartedness, afraid that someone would break their precious young heart. Stepping in to shelter and guard the heart of a young Two was the most loving way this adult could care for them. The problem was, the little Two’s fluency in gifting nurturing love was regularly mirrored by others with a similar quality of love. So, when a caregiver responded with protective love the young Two felt rejected, failing to comprehend protection as another way to express love. Subsequently, Twos doubled down on a nurturing stance in presenting love and determined this is how they’d eventually win back the love they gave away to the protective caregiver.

Type Three’s Closeness (Con)Fusion: Veneration vs. Adoration

When it comes to Threes, I really get gooey inside, feeling the pain they must never have given themselves permission to experience. The Threes’ ache is rooted in their Basic Fear and centers around questions like, “Am I really loved or just respected?” “Am I valuable enough to be loved or must I prove my worth?” These questions hollowed out their heart at a young age. Having fused the emptiness of their hearts with the closest nurturing heart they could find, they gave themselves over to what they perceive as valuable journeys of warranting self-acceptance through accomplishments in order to secure the love they desired. You see, Threes aren’t really preoccupied with winning or losing. They’re not really consumed with achievements. Nor are they narcissistically image conscious. They just want the emptiness of their hearts to be filled with love—a love that sees and affirms their intrinsic value. But as little kids they quickly realized when they performed well or were recognized for behaviors that were positively reinforced, something entered that hollowed-out heart center. Veneration became the low-hanging fruit they could substitute for real love. Their confusion around respect as an alternate for love led to an addictive drive to be seen, recognized, and accepted through their accomplishments. Because Threes fear they don’t have inherent worth, their Kidlife Crisis was a convoluted relationship to closeness—confusing veneration for pure adoring love.

Type Four’s Credibility Complex: Authenticity vs. Accuracy

The aching heart of the Four also wants to be known and loved but suffers their Kidlife Crisis as an experience of complex emotions that feel authentic; however, the circumstances assumed responsible for those feelings allow for multiple perspectives or alternative narratives. That’s not to diminish the depth of feeling associated with those memories. But it does require an accurate interrogation of how those memories are portrayed. Attuned to every detail of all things beautiful outside themselves, Fours can draw forward each splendid and magnificent facet in everything they encounter—everything and everyone but themselves. Unable to recognize their own beauty unearths a deep sense of frustration that is aimed at both the nurturing and protective caregiving energies in their imperfect holding environments. They perceive love to have been withheld, and frame this as the reason they can’t discover their own authentic selves. As a result, they inaccurately blame factors and forces outside themselves, causing those influences to suffer alongside them. The inaccuracy of how they remember their early holding environments can’t be challenged because their inner sense of being entirely authentic keeps them tethered to the illusions of what caused their loss of identity. This suffering, and the ways they pass it around, becomes a fatalistic cycle of staying distant from the truth that the source of their identity is love and it has actually never been withheld. The love that they want has always been with them; they’ve just felt disconnected from it. The very love they desire and the very love they’re born to share has always been there.

Type Five’s Controlled Constraint: Inside vs. Outside Containment

Much like Fours, those dominant in type Five are also heartbreakingly misunderstood. The misunderstanding of the Four is rooted in the depth and range of their emotional eloquence, while the misunderstanding of Fives is grounded in their brilliant cerebral skill. This one also breaks my heart because the Kidlife Crisis of the Five might be one of the most catastrophic misunderstandings of mismanaged attempts to offer and receive love. Generally, little Fives were fairly self-contained. They didn’t appear to require a lot of attention. Even as young children they possessed a savvy level of controlled constraint. To their caregiver, it appeared that their range of emotions were on a very tight and simple spectrum, even though their emotional world may have in fact run very, very deep. The competent inner control of the Five’s emotional life presented as a child with few needs and few demands. A relieved parent or thankful caregiver presumed their little Five required less shielding oversight and smothering care than perhaps another sibling needed or demanded. But in the mind of the young Five, the parental support of their perceived independence was a painful predicament which caused them to wonder what was wrong with them. Why didn’t they get to go out for ice cream after school like their peers or ride in the front seat with dad like their other siblings often did? Why were they left unattended more frequently than their sisters or brothers? What deficiency in them was the source of the distance they felt from their parent or caregivers? Seeking to understand all this, Fives brought these concerns inward (inner containment), examining and attempting to understand them, eventually concluding that they were actually just fine. Conversely, it had to be their caregiver or parents that were their problem, leading to the Five’s skillful outer containment. The missteps in feeling rejected and then rejecting is the accident of love acutely suffered as the Kidlife Crisis of Fives, a painful revolving door of unintended rejection.

Type Six’s Concern Collusion: Inner vs. Outer Authority Angst

Sixes value security and experience love when they feel safe. From an early age they looked to their caregiver to provide that sense of safety. They came to believe that if they colluded with their concerns and found a way to subvert any looming danger or potential threat, then they would experience love. Sixes experienced their Kidlife Crisis in relationship to their insecurities and who would ultimately keep them safe. They wanted to be taken care of by a protective presence who would allay all that fueled their apprehensions. The problem was that no one could dispel their fears for them. Disappointed and feeling let down by their outer authority, they turned to an anxious inner authority. Attempting to overcome their fears, instead they colluded with them. Concern collusion then led to a never-ending cycle of authority angst: “Who will protect me? The world isn’t safe. And if you won’t protect me and I can’t protect myself, then I’ll do everything I can to protect you.” They learned to do this through risk management as a means of getting the love they desired. The importance they place on security informed their ideas about how to care for their loved ones. This is why threat forecasting, contingency planning, and worst-case-scenario thinking are love languages for Sixes. The painful irony of their Kidlife Crisis is experienced in them by internalizing unreasonably severe outcomes for how bad things might get and doing this on behalf of everyone else, hoping we won’t have to suffer the consequences of their most outlandish worries.

Type Seven’s Crush Collection: Empty Heart vs. Full Imagination

Despite their difficulty in connecting with their heart, Sevens deeply want to love and be loved. As little kids this idealization for love was projected outside of them. They thought love would be found “out there.” So, they reached to the heart of a nurturing parent or caregiver (their first “crush”) to assist in their attempts to connect with their own heart. However, their insatiable curiosity caused them to easily grow bored of what held their attention in the present. Boredom led to frustration, and rather than take ownership of this, it was projected onto the source of their attention. Subsequently, Sevens moved from one crush to the next, consuming as much as their imagination enabled them to before tedious monotony set them in search of another heart to devour. Now, let me be clear, these “hearts” and “crushes” take the shape of anything that holds potential meaning—a person, an experience, an idea, a hobby, etc. Young Sevens didn’t set out to move from one infatuation to the next, nor do they desire this as adults. What’s happening behind the scenes here is their subconscious effort to avoid entering their own heart, which seems empty to them. Turning toward what appears to be an empty heart creates a fear that the pain of emptiness will be too much for them to bear. This Kidlife Crisis is one of running away from their inner agony while collecting premature painful departures from commitments that potentially could bring them back to their heart, where they might discover, after all, a fullness of love.

Type Eight’s Conflicted Conversion: Arrested vs. Accelerated Childhood

The Eight’s Kidlife Crisis has to do with their lost childhood. They grew up too quickly and yet a part of their growth was stunted, resulting in an unmistakable inner child. Young Eights perceived their vulnerability as weakness and therefore rejected the nurturing love of their caregiver. They are (metaphorically or actually) the child who didn’t want to be held. Presenting older or stronger than they actually were created a conflicted conversion. They converted to an older, stronger version of themselves before they were ready. This led to an arrested innocence—an inner child whose growth was stunted—and an accelerated childhood—they grew up too fast. This didn’t toughen them up, though Eights present as pretty tough. It merely fossilized an arrested development of the part of them that never fully matured. Those tender parts never got to come out and play because they felt like they needed to be stronger than they were ready to be. This is why you come across so many full-grown adult Eights innocently rocking their My Little Pony T-shirts, Star Wars action figure collections, or Hello Kitty lunchboxes—these accessories and toys are hooks to that arrested part of their childhood that had to prematurely solidify and is now trying to be reclaimed. The Eight’s Kidlife Crisis was a conflicted conversion, not in a religious sense, but more like a metamorphosis that skipped a step in the process of a child transforming into adulthood. It’s like the child who walked before they crawled. It might appear incredible, but the child must learn to crawl in order to meet critical aspects of childhood development. Likewise, as an adult, the Eight has to recover their vulnerability and learn how to meet those tender places with nurturing love to realize the wholeness that has been missing. As grownups, the residue of this Kidlife Crisis shows up in their struggle to be vulnerable. This is sometimes observed when they try to protect that tender place by presenting as lewd or combative, degenerate, or contrarian. Nearly all Eights demonstrate this through their need to be against something. Their difficulty with accepting their innocence is the painful reminder that they’ve misunderstood it as weakness, when all along it’s the source of their formidable strength.

Type Nine’s Compassion Compromise: Expressed vs. Repressed Love

Finally, we turn to the sensitivity of Nines who are born to be a source of love. They hold an incredible capacity of concern for others. That compassion is easily directed outward but leaves the Nine minimizing their own needs and desires. As children, their intuitive attunement to love needed an outward focus because turning that compassion inward seemed selfish—the opposite of the Nine’s gift for loving self-sacrifice. Their delicate sensitivities to those in their early holding environments became the focus of their attention, allowing young Nines to prioritize the needs of those around them, at the expense of their own. Their Kidlife Crisis was a trade-off entrenched in compassion—compassion for others but not for self. Learning to express love for everyone else only led to repressing love for themselves. Self-minimizing habitualized into self-forgetting, leading to an unconscious resentment or anger. The Nine’s anger is dormant because to acknowledge it would seem unloving to the Nine. How could expressing irritation be loving? Yet the denial of their own needs is the very source of their hidden resentments and masked anger.

***

If I’m honest, this is a struggle for me.

My folks were amazing; they went above and beyond what could have been expected of them. But realizing that my parents did their best to provide and care for me still doesn’t take away the impression of what may or may not have been missing. They did their best, and all I can do to honor that, as well as my imperfect humanity, is to live my best. And that sometimes means grieving the parts of myself that still need to be integrated into my whole, authentic self.

When this comes up with my psychotherapist (and yes, if you’re a parent you too will someday be the focus of at least a few therapy sessions . . .), he asks me to hold the fragment of myself that wants to belong, that wants more love, as if it were a crying baby who needs to be cared for. Demonstrating what he wants me to do, he’ll interlock his fingers palms upward and place his hands in front of his heart as if he’s holding an infant.

For a long time, this little gesture pissed me off.

No way was I going to put my hands together and cradle an imaginary baby, even my own projected inner child. Reluctantly, I’d try to hide an eye roll, quiet my frustrated exhale, and play along. Of course, it never worked for me because I wouldn’t let myself go there. My resistance to my own vulnerability made it impossible for me to make peace with what still hurt my inner child’s heart.

I was disgusted with my pain, but I wasn’t going to go there. That is, until I remembered a little girl who I used to take care of when I lived in India.

Immediately after completing university I moved to Chennai and helped start South Asia’s first pediatric AIDS care home for children orphaned because of the disease or born HIV+. At a time in my life when I should have been visiting the delivery rooms of my friends’ first children, I more frequently found myself at the gravesite of a small girl or boy we had buried way too early.

Because I was the only single person working at the home, I usually got called on to handle overnight shifts when we were understaffed. Rare as they were, when we needed help late at night it was usually because there was a sick child who needed extra attention. One such night we had just admitted an eight-month-old baby girl named Bimala.

She was adorable. She was also very sick. Her tiny undernourished body was covered in rashes, her back full of bedsores and blisters. Like many small HIV+ children, her mouth was full of open wounds.

I arrived at the home around 8 that night and would leave the next morning by 7. It wasn’t long before Bimala woke up the first time, sobbing in pain from all the ways she hurt. I picked her up trying to comfort her, and suddenly I felt a warm wetness on my chest that dripped down my stomach—urine everywhere. That was just the beginning. She was so sick with dysentery that I changed her diapers several times throughout the night.

Between short periods of rest, she kept waking up crying and crying. I’d try to keep her warm by holding her close to my body. Though I couldn’t take her pain away, I did everything I could think of to comfort her. I was shaken. It was awful. This poor child enduring unimaginable suffering, not able to make sense of it, and there was nothing I could do to alleviate it.

I just had to let her cry. I just had to be present to her. I just had to show her as much love as I could from my own broken heart.

Holding Bimala with compassion, embracing her with love, was an excruciating practice for learning to offer myself that same acceptance and care.

The next time my therapist asked me to cradle this fragmented part of myself, I thought of Bimala—honoring this small child so deserving of all love and care—and tried to practice presence genuinely.

Let’s attempt to bring this same compassion into how we cultivate an honest relationship with our type by briefly exploring nine compassionate blueprints for the different ways we express ourselves through personality.

Excerpt adapted from The Enneagram of Belonging: A Compassionate Journey of Self-Awareness by Christopher L. Heuertz. © 2020 by Christopher L. Heuertz. Published by Zondervan. Used by permission.

This article first first appeared in Enneagram Monthly Issue 252, February 2020. © Christopher L. Heuertz. Do not reprint or share without permission.

Photo Credit: Unsplash